Star Wars and the Phantom Celluloid (1999)

Witnessing the Dawn of Digital Cinema

Whatever you thought about the Star Wars prequel itself, the digital theatre experience we know today in 2022 was pioneered by this event:

… The world-premiere, first public demonstration of Texas Instruments’ new “digital light processing” (DLP) projection technology, in 1999.

(Article originally published in the Motion Picture Editors Guild magazine.)

Hopefully you had a chance to witness one of the recent digital screenings of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace during its experimental month-long run in Los Angeles and New York. We not only got a look at this cinema of the future, but also a peek behind the scenes …

A new century of digital cinema is upon us, and its inaugural took place in June on four screens nationwide, orchestrated by Lucasfilm’s THX division and CineComm Digital Cinema.

All told, two competing projection systems were demonstrated — a high-quality, though more conventional, analog system from Hughes/JVC; and Texas Instruments’ “DLP” (Digital Light Processing) system, which we were fortunate to see during its showing in Burbank.

So how did it look?

Well, the “film” — the word increasingly an anachronism — looked good. The picture was bright and clear, and eerily rock-solid on the screen. There were no distracting dirt or scratches to be seen.

There was, however, a certain amount of noise in the image, which varied widely from scene to scene … but since that was random and not “blockies” or “jaggies,” we were plainly seeing the grain in the original film used for the transfer, rather than a digital or compression artifact (random noise being the most difficult signal for a compression scheme to faithfully reproduce).

And with that realization, I had a sudden deja vu back to the debut of the Compact Disc — the theatre is now able, as the old disclaimer went, to reveal the deficiencies in the source material itself.

After the screening, one of the engineers from TI’s DLP projector development team showed a sample of the “digital micro-mirror device” (DMD) chips that were the product of twenty years of research.

A bona-fide work of nanotechnology, it looked somewhat like a microprocessor in a 2x2" metallic package.

On the front of the DMD was a 3/4" x 1" window that revealed a shiny silvery mirror of sorts — though under a microscope, you’d see an array of roughly 1.3 million individual microscopic mirrors. (It was the tiny gap between these mirrors, combined with the projector’s anamorphic lens, that had been the cause of one of the only visible artifacts: a vertical banding occasionally visible in the picture’s highlight areas, such as the credits and the white subtitles.)

Each mirror is aimed back & forth thousands of times per second, reflecting light either through the single projector lens and onto the screen, or away towards nothing.

By varying the percentage of time each of the tiny mirrors is pointed at the screen, it’s possible to create a luminance contrast ratio of 1000 to 1.

Three of the chips in tandem (for red, green & blue) meant roughly four million infinitesimal mirrors working feverishly in concert to bring us the vivid picture we’d witnessed.

But the big surprise was finding out that the resolution of these prototype chips was merely 1280 by 1024 pixels.

Thus, the picture we’d witnessed was actually inferior to HDTV, much to everyone’s surprise! (One engineer opined that because of the technology’s continued development, this experimental screening was therefore “the ‘worst’ digital cinema you’re ever likely to see.”)

“The Rack Behind the Curtain”

But what was the mysterious signal source feeding the projector’s voracious 1.5 gigabit per second appetite … tape, optical disc, satellite feed, or what? The answer: hard disk.

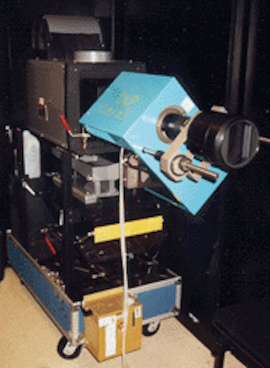

A peek inside the booth revealed a surprisingly modest half-rack of gear put together for this technology demonstration — containing an off-the-shelf Pluto Technologies HyperSpace RAID-3 array, with twenty 18GB drives; a Panasonic AJ-HDP500 HD-to-D5 hardware codec, capable of compressing a high-definition video signal down to about 360Mbps, a factor of roughly 4 to 1; and finally, a Tascam MMR-8 multitrack audio hard disk recorder, which supplied the six discrete channels of sound.

The picture had been telecine’d from an interpositive answer print at Modern Videofilm in Glendale, California, with a DLP projector specially set up so the colorist could see the resulting image projected in real time during the transfer.

The output of the Spirit Datacine was recorded onto a hi-def D5 tape, whose data was ultimately transferred to the disk array here in the booth — which was kept under special security, of course. This modest little rack of gear, after all, comprised a theatrical master-quality digital “print” of Star Wars: Episode I.

Leaving the theatre, and as an afterthought, I asked the woman behind the ticket counter whether there’d be any other films shown digitally in the near future (actually knowing better, but hoping nonetheless). Not for now, came the reply — “the whole thing’s really kind of new, you know?”

Of course, I knew. But now, I also knew that the future of cinema looked bright indeed.

Postscript, 2022

P.S. My one tangible souvenir from this special moment in cinema history actually did NOT come from T.I.’s headlining DLP demo in Burbank.

It was soon thereafter, from a showing of the competing CineComm projection system — fascinating in its own right.

A private event for a small group of industry insiders took place one quiet morning across the San Fernando Valley, in another theatre specially outfitted for the occasion.

It featured a split-screen demo of just the first reel of Phantom Menace: with digital projection on one side, and conventional film synchronized on the other. The sound was turned off the whole time, so participants could discuss and ask questions; that made the experience unique in itself.

And it was eye-opening to see, for the first time, the litany of filmic artifacts we’d gotten used to with celluloid for decades, laid bare by direct comparison to digital.

Texas Instruments, meanwhile, hadn’t thought to give out T-shirts for the occasion. As for my souvenir from CineComm, I’ve worn it proudly … though was a stickler for getting the chronology right. :)

Special thanks to Steven B. Cohen of Sony Pictures for the invitation to that, another small footnote in cinema history.

P.P.S. These historic digital screenings weren’t the first time Lucasfilm played a central role in the advancement of cinema, and helping lead filmmaking into the digital age.

For more, see my friend Michael Rubin’s excellent history, Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution.

Text and original images © Copyright 1999, 2022, Ron Diamond.

All rights reserved.